Poultry High Tech from 1887

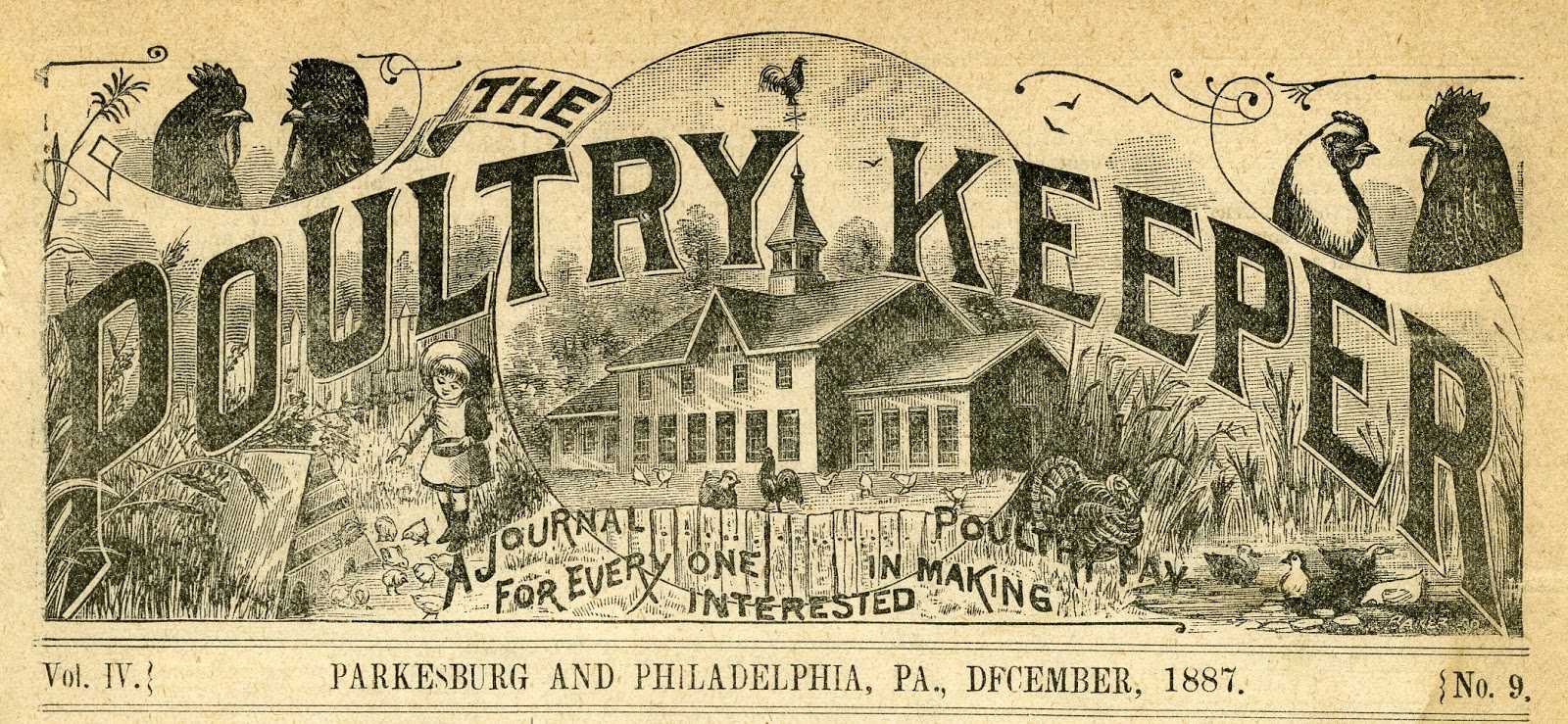

I recently came across a copy of an old magazine for poultry enthusiasts called The Poultry Keeper that was dated December, 1887. This journal for poultry

enthusiasts was published in Parkesburg & Philadephia, Pennsylvania and

was created for people who were “interested in making poultry pay," or so says the banner.

Then as now, there was a good deal of interest in

do-it-yourself projects. Perhaps, back then chicken owners really didn’t have

much of a choice; you made it yourself or you did without.

Let’s remember that in 1887 most men who

fought in the civil war were still alive, over 40% of American’s lived on farms

(versus 2% today), and the first Sears Roebuck catalog wouldn’t be published until the following year. If you

didn’t build it yourself, you didn’t

have it.

Two small articles in the Poultry Keeper describing DIY

projects caught my eye. I thought it would be fun to share these with you. They

represent “high” tech poultry equipment design for the time.

Incubator Project

An incubator is a device that keeps fertilized eggs warm so

that chicks can be hatched. Nowadays, a number of companies make very good

electric units for home enthusiasts. These incubators include both a heating element and a thermostat. Plug them in, and they’re ready to go.

But in 1887, it wasn’t that easy…..

People had to build their own incubators and so The Poultry

Keeper provided design ideas and simple instructions. One design used hot air

to warm the incubator and a second design used hot water. That notwithstanding,

both function in pretty much the same way.

An oil lamp is used as a heat source and functions like a

boiler. It heats either air or water, that is then allowed to circulate into a

chamber within the incubator to provide heat. If you’ve ever lived in a house

that was heated by a steam radiator, you’ll understand exactly how these

systems work.

The design shown below is the hot air system. A tin cone

connected to a pipe is placed over the globe of an oil lamp. Heat generated by

the oil lamp is transmitted to the air within the lamp and is allowed to circulate

into the top of the incubator by way of the pipe.

The second design is similar, but here a water chamber is constructed

to fit over the globe. The lamp heats water in the chamber and this then

circulates into a water tank within the incubator. The

water is then recirculated -- Cooler water in the incubator is driven into the

lover part of the lamp’s water chamber where it is re-heated and driven back

into the incubator.

A Primitive Thermostat

In the same issue, a reader, Mr. G. A. Hayne of Dagerville,

Iowa sent a drawing of a “regulator” that could be placed within the incubator

to help control the temperature.

However, unlike today’s thermostats, this

device did not automatically adjust the temperature. Rather, it sounded an

alarm that would let the chicken owner know that the brooder was either too hot

or too cold. The owner would then need to manually adjust the wick within the

lamp to either increase or decrease the heat.

Here’s how it worked…….

In figure #1 (cross-sectional view of the regulator) a bell [B] is connected to what appears to be a battery [L]. When a connection is made between the two

polls of the battery, current runs through the circuit and causes a bell to

ring. There is a switch [R] that sits between the two poles of the battery that is

temperature sensitive. This switch is the heart of the “regulator.”

It is constructed of a thin sheet of metal riveted to a thin

sheet of rubber. The rubber expands or contracts depending on the temperature

in the environment. Therefore, it will either bend upward or downward. The

extent of the bending depends on the temperature in the ambient environment. If

it bends in either direction sufficiently (In other words the temperature is too

hot or too cold) the metal end of the regulator will come in contact with one

of two metal screws [I and J]. When this contact occurs, the circuit is closed and allows

electricity to flow from the battery to the bell, sounding an alarm that calls

the owner over to make an adjustment to the oil lamp.

To make the system work, you only need to set the right distance

between the two screws and the metal/rubber switch. This is done by setting the lower and upper

temperatures using a thermometer.

When the temperature is at the lower limit,

you turn one of the screws till it just touches the metal sheet (causes a connection).

Then turn up the heat and wait till the temperature reaches the upper limit of

what you want and then turn the second screw till it just touches the metal

sheet (causes another connection). The regulator is now set to ring whenever

the temperature changes beyond the upper and lower temperature limits.

Would this contraption work? I think so! Modern thermostats

operate along pretty much the same principle but instead of a metal sheet, the

connection is made using a bubble of liquid mercury (like that used in an oral

thermometer). When the temperature increases, the mercury expands and creates

an electrical connection that turns on your heating unit.

How accurate would it be? It really depends on the materials

you use. However, in 1887 it would have been as high tech as it gets. Nest

Thermostat move over!

Comments

Post a Comment